Barbarogenies of the Digital Age: From Zenitism to Gen Z Students of Serbia

How a century-old Balkan avant-garde predicted today's student uprising

October 1, 2024. The canopy of Novi Sad's railway station collapses under the weight of corruption, and with it fall the last illusions about a system that has cultivated a culture of irresponsibility for decades. Fifteen lives extinguished in a second. But from this tragedy, as often happens in Balkan history, something unexpected is born. December 2024: students across Serbia rise up, one faculty after another joining the rebellion. They block universities, stop traffic, refuse to be silenced. They don't seek leaders. They don't carry party flags. They carry only the pain and rage of a generation that has said: enough.

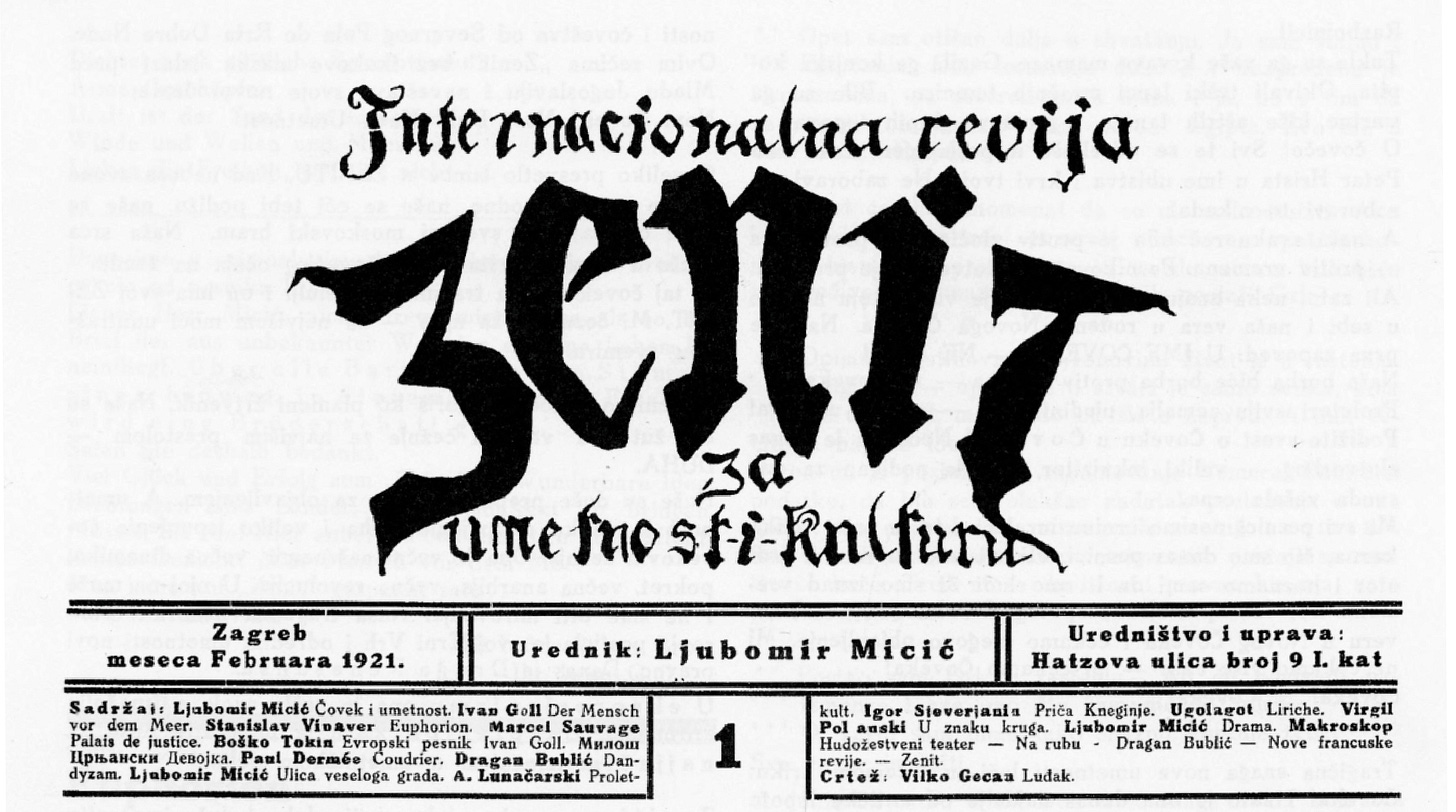

One hundred years earlier, February 1921. In the same land, only differently named (the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes), a group of young intellectuals launched a magazine that would become the epicenter of one of Europe's most radical avant-garde ideas. Zenit. A name suggesting the zenith, the highest point of the sun's trajectory. But for Ljubomir Micić and his collaborators, it was a point from which one could throw stones at god, as he himself wrote. These were young people who had survived World War I and watched as Europe, that self-proclaimed cradle of civilization, decomposed in its own blood and mud.

The Serbian Singularity

Before we dive deeper into this historical parallel, let's be clear: the Gen Z Students of Serbia are not merely a local manifestation of a global generational phenomenon. While they may share the demographic bracket with their peers worldwide, their uprising is distinctly Serbian, rooted in specific historical trauma and political context that makes them unique. This is not about TikTok trends or avocado toast. This is about a generation born after Yugoslavia's collapse to parents who carry traumas of a destroyed country and NATO bombing in 1999: children of the 21st century who inherited a broken system.

The zenitists understood this kind of specificity. When Ljubomir Micić proclaimed "Balkanization of Europe, not Europeanization of the Balkans," he wasn't speaking to or for a global audience. He was articulating a distinctly Balkan response to European modernity. Similarly, when Gen Z Students of Serbia organize through plenums and refuse hierarchical leadership, they're not copying Occupy Wall Street or global protest movements. They're not even drawing on the tradition of domestic protests from 1968 and 1996-97. Instead, they're writing entirely new rules, creating a form of resistance that is uniquely theirs.

Balkanization as Manifesto

"Balkanization of Europe, not Europeanization of the Balkans": the slogan Micić inscribed as a battle cry for a new era. Today, when the term is used as a synonym for fragmentation and chaos, it's difficult to understand the revolutionary charge it carried. For the zenitists, balkanization wasn't destruction but regeneration. It was the idea that the Balkans, eternally marginalized and treated as Europe's periphery, actually possessed a vitality that could save a faltering Europe.

Barbarogeny: the hybrid figure Micić constructed as a symbol of the new Balkan man. Neither barbarian nor genius, but both simultaneously. This wasn't a romantic return to primitivism, but a radical re-examination of the hierarchy of values. If civilized Europe could produce the hell of World War I's trenches, perhaps it was time to reconsider barbarism as an alternative.

The zenitists weren't alone in their rebellion. The magazine gathered collaborators from Marinetti to Mayakovsky, from Kandinsky to El Lissitzky. But what made Zenit unique was its Balkan perspective: a view from the margins that refused to accept marginality as destiny. Instead of imitating Paris or Berlin, they claimed the Balkans had something to offer the world.

Architecture of Rebellion

The structure of the zenitist movement was chaotic, fragmentary, contradictory. Micić was simultaneously expressionist and constructivist, internationalist and nationalist. The zenitist manifesto called for the destruction of the old and construction of the new, but it was never clear what exactly this new should be. Perhaps this very indefiniteness was their strength: a refusal to be pigeonholed into existing categories.

The magazine was shut down in 1926, after authorities banned its operation. Micić went into exile in Paris, where he would spend nine years trying to reanimate zenitism in a new environment. But the time of manifestos and avant-gardes had passed. Europe was preparing for a new war, and the utopian visions of the twenties seemed naive in the shadow of fascism looming over the continent.

Digital Barbarogenies

Fast forward to the present. The students blocking faculties belong to what demographers call Gen Z: the first generation never to experience life without the internet. But let's be precise: these are Gen Z Students of Serbia, and their struggle cannot be understood through the lens of global generational theory. If the zenitists were children of war and revolution, these students are children of a specific post-socialist, post-conflict transition that went horribly wrong.

The parallels with zenitism are obvious, but so are the differences. Like the zenitists, Gen Z Students of Serbia reject hierarchies. The student protests insist they have no leaders. Decisions are made at plenums, through consensus. There's no cult of personality, no charismatic leaders. Just a collective speaking with one voice.

Their medium isn't a printed magazine but Instagram and TikTok. Yet the logic is the same: bypass established channels of communication, create your own network. But here's where the Serbian specificity matters: while Gen Z globally uses social media for self-expression and consumption, Gen Z Students of Serbia have weaponized it for resistance. Every faculty has its Instagram account, every blockade its hashtag. Information spreads at the speed of light, and a government accustomed to controlling traditional media remains powerless before this decentralized network.

Silence as Performance

The most striking moment of the protests: fifteen minutes of silence for fifteen victims. Every day at 11:52, the time when the canopy collapsed, those who stand with the students stop in solidarity. This isn't just commemoration; it's a form of political theater the zenitists would have appreciated. Silence that screams louder than any slogan.

But unlike the zenitists who were intoxicated with words, manifestos, declarations, Gen Z Students of Serbia are skeptical of grand narratives. They don't offer a vision of a new world. They don't promise utopia. Their demands are concrete, almost prosaic: publish the documentation, establish responsibility, punish the attackers, increase the education budget.

Perhaps this reflects our times. After the collapse of all the great ideologies of the twentieth century, only the struggle for basic decency remains. For a system that functions. For accountability.

Time Without Illusions

The zenitists believed they could change the world. Micić's barbarogeny was supposed to be the herald of a new era, a figure that would bring "creative genius and freshness" to tired Europe. That faith in art's power to transform reality seems almost touchingly naive today.

Gen Z Students of Serbia have no such illusions. They grew up in a world of economic crisis, pandemic, climate change. But more specifically, they grew up in a Serbia where every institution has been hollowed out, where corruption isn't an aberration but the system itself. Their activism isn't based on faith in a bright future but on the awareness that the alternative simply isn't an option. The struggle isn't a choice but a necessity.

But perhaps that's precisely their strength. Freed from the burden of grand narratives, they can focus on the concrete, immediate, tangible. Instead of manifestos, they write demands. Instead of visions, they offer procedures. Instead of leaders, they create networks.

The Weight of History

What can Gen Z Students of Serbia learn from the zenitists' failure? The zenitist movement lasted only five years, from February 1921 to December 1926. Brief, intense, like a torch burning too brightly to last long. Micić lived another 45 years after the magazine's closure, but never again managed to repeat that moment of creative explosion.

The zenitists failed in their primary mission: to enlighten the unenlightened masses, to transform the Balkans into a cultural force that would regenerate Europe. Their ideas remained confined to a small circle of intellectuals, never penetrating the broader society they sought to transform. The barbarogeny remained a literary figure rather than a social reality.

This is perhaps the crucial lesson for Gen Z Students of Serbia. The zenitists were brilliant at creating alternative cultural spaces but failed to translate that energy into lasting institutional change. They were masters of symbolic politics but amateurs at actual politics. They could imagine new worlds but couldn't build them.

Networks Without Centers

Yet there's something in the zenitist experiment that resonates with the current student movement. When a Gen Z student of Serbia says it's important "that every faculty's voice is heard, that no faculty positions itself as leader," he perhaps unconsciously echoes Micić's vision of a culture that isn't hierarchical but rhizomatic, that doesn't flow from center to periphery but creates multiple centers.

This is where Gen Z Students of Serbia might succeed where the zenitists failed. Their horizontal organization, their refusal of leadership, their insistence on consensus: these aren't just tactical choices but a fundamentally different way of thinking about power and change. They're not trying to storm the palace; they're trying to make the palace irrelevant.

The zenitists, for all their radicalism, still believed in the avant-garde model: a small group of enlightened artists leading the masses toward a new consciousness. Gen Z Students of Serbia have no such pretensions. They don't see themselves as an enlightened vanguard but as citizens demanding basic rights. This modesty might be their greatest strength.

The Continuity of Rupture

Is there a connection between the zenitists and today's Serbian students? On the surface, little connects them. One group consisted of modernists obsessed with the new; the other, postmodernists aware that the new no longer exists. One believed in avant-gardes; the other in horizontal networks. One wrote manifestos; the other organizes plenums.

But beneath the surface, there's a deeper continuity. Both represent generations that said "no" to a system that betrayed them. Both tried to create alternative spaces for action when all existing channels were blocked. Both insisted on the right to be subjects, not objects, of history.

And both emerged from specifically Serbian/Yugoslav contexts that shaped their rebellion. The zenitists responded to the particular trauma of World War I as experienced in the Balkans: not just the Western Front's mechanized slaughter but the complex ethnic violence that would prefigure Yugoslavia's later tragedies. Gen Z Students of Serbia respond to the particular trauma of a failed transition, of promises broken and futures stolen.

The Last Act

Zenitism lasted only five years. From February 1921 to December 1926. What will happen to the Gen Z Students of Serbia revolution? Will it become just another in a series of student protests that thundered through Serbia only to fade without a trace? Or might it succeed where the zenitists failed: in transforming the energy of rebellion into lasting change?

We don't know the answer. But perhaps that's not what matters. Perhaps the very fact that they rose up, that they said "no," that they showed an alternative exists: perhaps that's enough. Because every generation must find its own way to oppose the forces that suffocate it. Every generation must become its own barbarogeny.

But here's what's different this time. The zenitists were, ultimately, elitists. They believed in the transformative power of art and culture, but that transformation was to flow from the enlightened few to the ignorant many. Gen Z Students of Serbia make no such claims. They don't position themselves as cultural or intellectual superiors. They simply demand that the system work as it claims to work. They want documentation made public. They want those responsible held accountable. They want their universities properly funded.

In this modesty lies perhaps a greater radicalism than anything the zenitists imagined. Because while the zenitists wanted to create a new world, Gen Z Students of Serbia are doing something more subversive: they're taking the existing system at its word. They're saying: you claim to be a democracy, so act like one. You claim to believe in rule of law, so apply it. You claim to value education, so fund it.

Digital Barbarism

November falls on Novi Sad station. The whole country stops in silence. Somewhere in that silence, the echo of Micić's words can be heard: "And we'll still writhe on godly gallows / Aman / But new pains will be avenged by barbarogenies." A poem written a hundred years ago sounds like prophecy. Or perhaps like a promise.

Because the barbarogenies are returning. No longer with manifestos and avant-garde magazines, but with smartphones and Instagram accounts. And no longer with visions of new civilization, but with simple demands for justice. But at its core, it's the same struggle: the struggle for the right to be human in a system that insists you be a number.

And so the circle closes. From Zenit to Gen Z Students of Serbia. From manifestos to memes. From utopia to basic decency. Different times, different media, but the same need: to stand up and say: this can't go on.

Maybe that's what the zenitists wanted to say too. They just used more words. Maybe every generation is doomed to rediscover the same truth: that freedom isn't given but won, again and again, in an endless struggle against forces that would reduce us to obedient subjects.

In that sense, we are all barbarogenies. We all carry within us that duality: the civilization that makes us conformists and the barbarism that makes us free. The question is only whether we'll have the courage to liberate that inner barbarian.

Gen Z Students of Serbia have shown they have that courage in a society that seems hopelessly corrupt, cynical, and lost; it's possible to say: no more. They've created their own Zenit moment: not in an avant-garde magazine but in the streets and corridors of their universities.

Now it's up to the rest of society to decide: to stand with them or, as always, wait for the storm to pass?

The answer to that question may determine not only Serbia's future but whether we'll finally manage to realize the vision the zenitists only glimpsed: a Balkans that isn't margin but center, that doesn't imitate but creates, that doesn't follow but leads.

The barbarogenies of Serbia have risen.

Notes:

This analysis is part of a series written from the perspective of a professor witnessing the Gen Z Students of Serbia movement. State universities in Serbia have been shut down since December 2024. Professors have been penalized and haven't received salaries since February. State universities are Serbia's intellectual brand, funded by the state budget, owned by all citizens. Today, everything is possible. Tomorrow, we'll see.

© 2025 Biljana Arandelovic. All rights reserved. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.